National

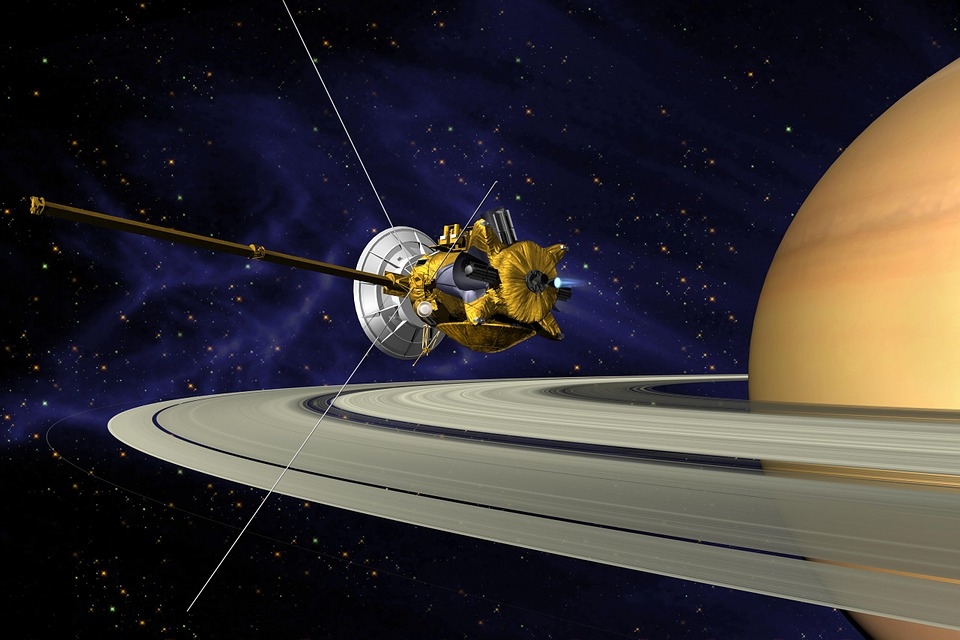

Cassini spacecraft: ‘Magnifying glass’ at Saturn until end

Cassini rocketed from Cape Canaveral in 1997 on

what was supposed to be a four-year mission

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. — For more than a decade, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft at Saturn took “a magnifying glass” to the enchanting planet, its moons and rings.

Cassini revealed wet, exotic worlds that might harbor life: the moons Enceladus and Titan. It unveiled moonlets embedded in the rings. It also gave us front-row seats to Saturn’s changing seasons and a storm so vast that it encircled the planet.

“We’ve had an incredible 13-year journey around Saturn, returning data like a giant firehose, just flooding us with data,” project scientist Linda Spilker said this week from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “Almost like we’ve taken a magnifying glass to the planet and the rings.”

Astrophysicist Katie Mack is interviewed about the spacecraft below.

Today’s the day. In just under seven hours, the Cassini spacecraft, which has brought us incredible views of the planet, its rings, and its amazing moons, will end its mission, plunging into the giant planet’s atmosphere and vaporizing in a blaze of glory. This is the Cassini mission’s #GrandFinale. Over its 13 years in the Saturn system, Cassini and its Titan-lander Huygens have brought us an invaluable treasure-trove of scientific insights, along with a vast library of over 400,000 breathtakingly beautiful images. It has shown us that at least two of the moons of the gas giant have liquid water oceans under their surfaces, making them some of the best places to search for signs of life in our Solar System. It has shown us dramatic atmospheric structures in Saturn’s atmosphere (such as the striking polar hexagon) and has given us clues to understanding how the rings and moons formed. It has tasted the icy plumes escaping from Enceladus’s sub-surface ocean, and the Huygens probe has shown us that the surface of Titan is a complex landscape of lakes and islands, with water-ice pebbles and methane seas. Both Titan and Enceladus have similarities with the early Earth — learning more about these moons has given us tantalizing hints about our own origins as a life-bearing world. Unfortunately, the mission must come to an end. Cassini has already lasted far longer than its 4-year primary mission, and it is now almost entirely out of fuel. Rather than being left in orbit, where a chance encounter could send it crashing into one of the moons (potentially contaminating any life that might be there), Cassini is now on a collision course with Saturn. Very soon it will impact Saturn’s atmosphere, taking data as long as it can keep its antenna pointed at the Earth, before it succumbs to the pressures and temperatures of its high-velocity dive. You can read more about the mission and the Grand Finale at JPL’s official Cassini webpage: https://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/ and links to sites where you can watch the final signals come in live are here: https://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/grand-finale/for-media/?admin_preview=true#streaming NASA has also released a free e-book with images from the mission here: https://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/resources/7777/?category=graphics I’ve written a story for Cosmos Magazine about why the effort to protect life in the Universe means Cassini has to die: https://cosmosmagazine.com/space/why-planetary-protection-means-cassini-must-die And if you’d like to watch me breathlessly attempt to cover all of Cassini’s amazingness in a 7.5-minute live TV interview, you can watch the video attached. (And to see one of the ways Cassini has inspired me, see this post: https://www.facebook.com/astrokatie/photos/a.390161034448324.1073741828.388381527959608/941919262605829/?type=3)

Posted by AstroKatie – Katie Mack on Thursday, September 14, 2017

Cassini was expected to send back new details about Saturn’s atmosphere right up until its blazing finale on Friday. Its delicate thrusters no match for the thickening atmosphere, the spacecraft was destined to tumble out of control during its rapid plunge and burn up like a meteor in Saturn’s sky.

A brief look back at Cassini:

___

TIMELINE: Cassini rocketed from Cape Canaveral, Florida, on Oct. 15, 1997, carrying with it the European Huygens lander. The spacecraft arrived at Saturn in 2004. Six months later, Huygens detached from Cassini and successfully parachuted onto the giant moon Titan. Cassini remained in orbit around Saturn, the only spacecraft to ever circle the planet. Last April, NASA put Cassini on an ever-descending series of final orbits, leading to Friday’s swan dive. Better that, they figured, than Cassini accidentally colliding with a moon that might harbor life and contaminating it.

SPACECRAFT: Traveling too far from the sun to reap its energy, Cassini used plutonium for electrical power to feed its science instruments. Its separate, main fuel tank, however, was getting low when NASA put the spacecraft on the no-turning-back Grand Finale. The mission already had achieved great success, and despite the chance of pounding Cassini with ring debris, flight controllers directed the spacecraft into the narrow gap between the rings and Saturn’s cloud tops. Cassini successfully sailed through the gap 22 times, providing ever better close-ups of Saturn.

RINGS: Cassini discovered swarms of moonlets in Saturn’s rings, including one called Peggy that made the short list for final picture-taking. Scientists wanted one last look to see if Peggy had broken free of its ring. Data from the spacecraft indicate Saturn’s rings — which consist of icy bits ranging in size from dust to mountains — may be on the less massive side. That would make them relatively young compared with Saturn; perhaps a moon or comet came too close to Saturn and broke apart, forming the rings 100 million years ago. Or perhaps multiple such collisions occurred. On the flip side, more massive rings would suggest they originated around the same time as Saturn, more than 4 billion years ago.

MOONS: Saturn has 62 known moons, including six discovered by Cassini. The biggest, by far, is the first one discovered way back in the 1655: Titan, which slightly outdoes Mercury. Its lakes hold liquid methane, which could hold some new, exotic form of life. Little moon Enceladus is believed to have a global underground ocean that could be sloshing with life more as we know it. Incredibly, geysers of water vapor and ice shoot out of cracks in Enceladus’ south pole. Project scientist Linda Spilker said if she could change one thing about Cassini, it would have been to add life-detecting sensors to sample these plumes. But no one knew about the geysers until Cassini arrived on the scene.

NEXT UP: Scientists would love to return to Enceladus or Titan to search for any potential life. Nothing is firmly on the books right now. But there are proposals to go back, submitted under NASA’s New Frontiers program. So stay tuned.