National

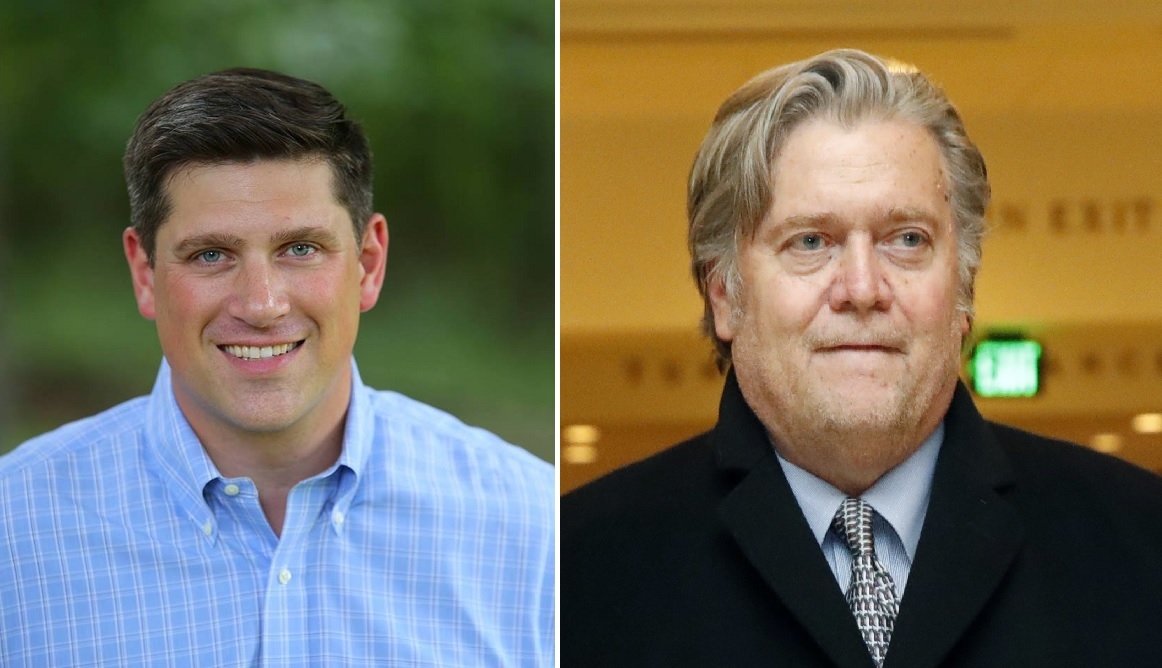

Once an outsider’s badge of honor, Steve Bannon backing now tricky

Some Republican Senate candidates who once trumpeted the blessing of former White House adviser Steve Bannon are now denying he ever endorsed them.

Once seen as coveted validation with Republicans’ unsettled base, Bannon’s backing has become a predicament for some since his falling-out with President Donald Trump. A number of conservatives have abruptly found themselves caught between a high-profile ally and a president who prizes loyalty above all else.

The most recent example of the awkward sidestepping came from U.S. Senate candidate Kevin Nicholson of Wisconsin. Asked last week by a Milwaukee radio host whether Bannon’s support still had value, Nicholson offered a distinction.

“The endorsement that I received is actually from the Great America PAC,” he said, noting that former Ronald Reagan adviser Ed Rollins, not Bannon, is chairman of the group.

“That’s the kind of person I want on my side,” Nicholson said. “And I’ll absolutely take the help of Ed Rollins.”

Indeed, Rollins is the group’s head, though that was not how Nicholson described the endorsement when it first landed.

“Excited to receive an endorsement from the Great America PAC and Steve Bannon,” he tweeted in October.

Nicholson aides emphasize that Rollins remains head of the PAC and that Bannon’s role in the group has changed since the fall, when Nicholson and other candidates met with Bannon to seek the group’s endorsement. Great America PAC says Bannon never had any formal involvement.

Nicholson, a suburban Milwaukee businessman and former Marine, is competing against state Sen. Leah Vukmir, who has the support of former White House chief of staff Reince Priebus and those close to Republican Gov. Scott Walker, including his former campaign manager and his son.

He is one of six Republican Senate candidates endorsed by the pro-Trump group, which boasted close ties to Bannon last year but has since said he never had any formal ties. The group also endorsed losing Alabama Senate candidate Roy Moore, who had been accused of sexually assaulting teenage girls decades ago.

Bannon, fired as a senior White House adviser in July, re-emerged last fall pledging to topple Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell by recruiting and backing Republicans challenging virtually every GOP senators seeking re-election in 2018. It was an effort, he said, to ensure Trump’s agenda.

Moore’s defeat hobbled Bannon. But it was the release of Michael Wolff’s book weeks later quoting Bannon as sharply criticizing Trump family members that set off a wave of Republican disavowals, led by Trump himself.

While Nicholson and others have described Bannon’s comments as inappropriate and serious mistakes, they have also downplayed the value of his support, going as far as attempting to strike it from the record entirely.

“I don’t know that I actually got a full endorsement from Steve,” Arizona Senate candidate Kelli Ward said during a CNN interview this month. As with Nicholson, Great America had endorsed Ward in October.

Bannon had played a more public role in Ward’s campaign than Nicholson’s, appearing at her October campaign kickoff rally in Scottsdale, where he called her “a whirlwind.” Ward later described the appearance as “wonderful.”

Yet, after listing Bannon on a campaign press release in November as among her national backers, Ward’s campaign has since stricken his name and omits him when ticking through her prominent supporters during interviews.

Since the Dec. 12 Alabama election, and even more so since the public break with Trump this month, Bannon has kept a low profile.

Bannon apologized days after the Wolff book was released, but he was stripped of his job leading the pro-Trump news website Breitbart News.

Iowa Republicans, who had tentatively planned to have Bannon speak at the state’s largest county GOP fundraiser this month, lost interest after Trump’s renunciation and dropped the plans.

It’s a stunning reversal from the closing months of 2017, when Bannon headlined the California Republican Party convention, marked the anniversary of Trump’s election at a suburban Detroit county GOP banquet, spoke at Ward and Moore campaign events and defiantly declared at the Values Voters Summit in Washington, “Right now, it’s a season of war against a GOP establishment.”

Some of Bannon’s chosen candidates have more subtly distanced themselves.

Montana state Auditor Matt Rosendale proclaimed Bannon’s endorsement by tweeting a picture of the two together. However, in recent online ads listing his endorsements, he does not include Bannon.

“When Steve Bannon speaks, people listen,” Nachama Soloveichik, spokeswoman for West Virginia Republican Patrick Morrisey, said after Bannon endorsed him for Senate in October. “If Steve Bannon wants to help spread Patrick’s conservative message, he can be a tremendous help and make a big impact on this race.”

Last week, while not disavowing Bannon, Soloveichik said, “We are not touting his endorsement and have been focusing on our support of President Trump.”

Tennessee Rep. Marsha Blackburn, the choice of Senate leadership and Bannon, has been an outlier, neither acknowledging publicly Bannon’s endorsement nor commenting since his break with Trump.

Those familiar with Great America’s operations have downplayed Bannon’s influence as some of the candidates have, suggesting Bannon never had any formal ties to the group.

The super PAC had not attempted to correct news coverage that linked it with Bannon because Great America benefited from the spotlight’s attraction to him.

Since the backlash, however, the group has quietly sought to set the record straight.