National

McConnell’s year-end wish: Getting Congress to legalize hemp

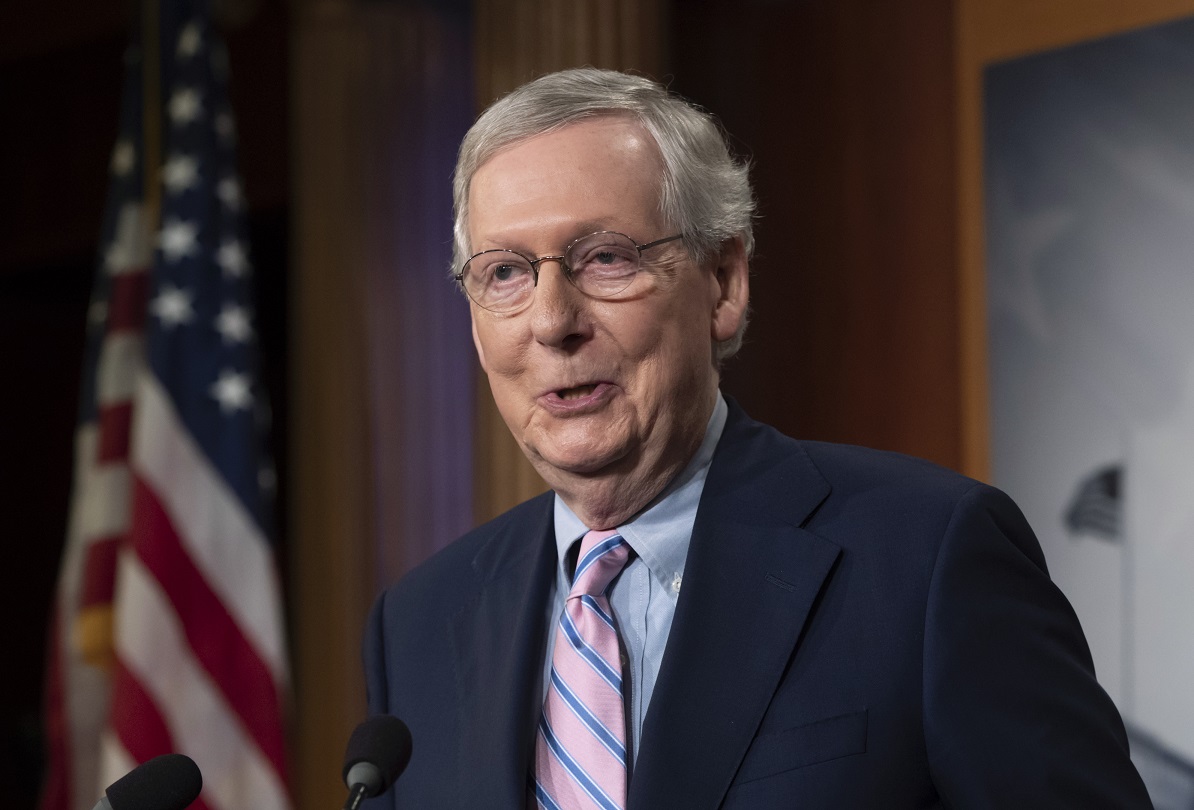

LOUISVILLE, Ky. (AP) — Pressed for time and pushed to move quickly on a border wall and criminal justice reform, the Senate’s top leader has his own priority in Congress’ lame-duck session: passing a farm bill that includes a full pardon for hemp, the non-intoxicating cousin of marijuana that’s making a comeback in his home state.

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has guaranteed that his proposal to make hemp a legal agricultural commodity, removing it from the federal list of controlled substances, will be part of the final farm bill, a crucial measure for rural America and Kentucky, where the Republican senator faces re-election in 2020. He places it on a par with federal spending bills as action Congress must take before the end of the year.

Keeping that promise would cap a decadeslong journey to overcome the stigma associated with the crop, which McConnell himself did not initially embrace wholeheartedly. But in recent years, the quintessential establishment Republican has been all in for the hemp revolution.

McConnell put himself on the conference committee assigned to negotiate a compromise farm bill. Work requirements for food stamps, known as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, have been the biggest stumbling block holding up an agreement.

Kentucky has emerged as a leader in developing a hemp industry and as a place where legalizing the crop went from a fringe issue to a mainstream cause. Fellow Kentucky Republican Sen. Rand Paul and Republican U.S. Reps. Thomas Massie and James Comer are strong supporters, too.

But it’s McConnell’s backing that has put the long-banned crop on the verge of winning a full pardon.

“We are very fortunate to have Sen. McConnell as our top advocate in Congress,” said Eric Steenstra, president of the hemp advocacy group Vote Hemp.

Comer, a leading hemp proponent since his days as Kentucky’s agriculture commissioner, likes the provision’s chances this year.

“It’s going to happen,” he said.

Hemp is deeply rooted in Kentucky’s past dating back to pioneer days. But growing hemp without a federal permit was banned decades ago because of its classification as a controlled substance related to marijuana. Hemp and marijuana are the same species, but hemp has a negligible amount of THC, the psychoactive compound that gives marijuana users a high.

The crop was historically used for rope but has many other uses, including clothing and mulch from the fiber; hemp milk and cooking oil from the seeds; and soap and lotions. Other uses include building materials, animal bedding and biofuels. Hemp-derived cannabidiol, or CBD oil, as a health product has become an increasingly large market.

Hemp’s comeback started with the 2014 federal farm bill. McConnell helped push for a provision allowing states to pursue hemp research and development. That allowed the crop to be grown on an experimental basis.

“They (hemp proponents) did a nice job of figuring out how to explain the marketplace for this to make this seem like something other than a pie-in-the-sky, fringe idea,” said Scott Jennings, a Kentucky-based Republican consultant with close ties to McConnell. “And McConnell listened and found his way to supporting them because they made a good case.”

In helping push hemp into the mainstream, McConnell reached out to allay law enforcement concerns about the crop, Jennings said. The senator talks publicly about the differences between hemp and marijuana.

It’s not the first time McConnell has been a key player in potentially transforming Kentucky agriculture. More than a decade ago, the Republican lawmaker helped win the multibillion-dollar tobacco buyout, which compensated U.S. tobacco growers and others for losing production quotas when the government’s price-support program ended.

Hemp production has spread since its modest beginning in 2014, when 33 acres (13 hectares) were planted in Kentucky. Kentucky farmers planted 6,700 acres (2,710 hectares) of hemp in 2018— more than twice last year’s production, according to the state’s agriculture department. More than 70 Kentucky processors are turning the versatile plant into products.

“Industrial hemp is no longer a novelty in Kentucky but is emerging as a commodity with a viable economic success,” said current Kentucky Agriculture Commissioner Ryan Quarles.

Nearly 78,000 acres (31,500 hectares) of hemp were grown nationally this year, up from nearly 26,000 acres (10,500 hectares) in 2017, with Montana, Colorado and Oregon joining Kentucky as top 2018 producers, according to Vote Hemp.

Hemp products sold in the U.S. had an estimated retail value of at least $820 million in 2017, the group said. With limited domestic production allowed by law, most hemp is imported. If domestic hemp production wins legalization, those sales will soon eclipse $1 billion and keep growing, Steenstra said.

“This is huge,” he said. “The farm bill hemp provision is going to provide a much-needed regulatory certainty for the market. We’ve got a lot of people that are interested in investing in this but have been sitting on the sidelines.”

In Kentucky, the road toward hemp legalization was bumpy. Law enforcement put up stiff resistance to Kentucky’s legislation in 2013 to set up a framework to allow hemp pilot projects once the federal government lifted restrictions on the plant. Comer recalled a shouting match erupting as the bill was pitched behind closed doors to some Republican lawmakers.

Then, in the spring of 2014, as Kentucky farmers prepared to plant the first legal hemp crop in decades, a court fight broke out when imported hemp seeds were detained by federal authorities. The state’s agriculture department, then led by Comer, sued the federal government. The seeds eventually were released after federal officials approved a permit and an agreement was reached on importing seeds into Kentucky.

Now, development of a hemp industry has “exceeded my wildest expectations,” Comer said. But there were anxious times in the early days.

“My fear was it would be a bust and it would never amount to anything,” Comer said. “And people would say, ‘Well, you spent a lot of time and energy for nothing.’ But I don’t think there’s anybody in America that would say that fight wasn’t worth it. Because it’s just really created a lot of opportunities.”