National

AP Explains: What a Trump impeachment trial might look like

WASHINGTON (AP) — As House Democrats quickly move forward with impeachment proceedings, the likelihood grows that Donald Trump will become the third president to face a Senate trial to determine whether he should be removed from office.

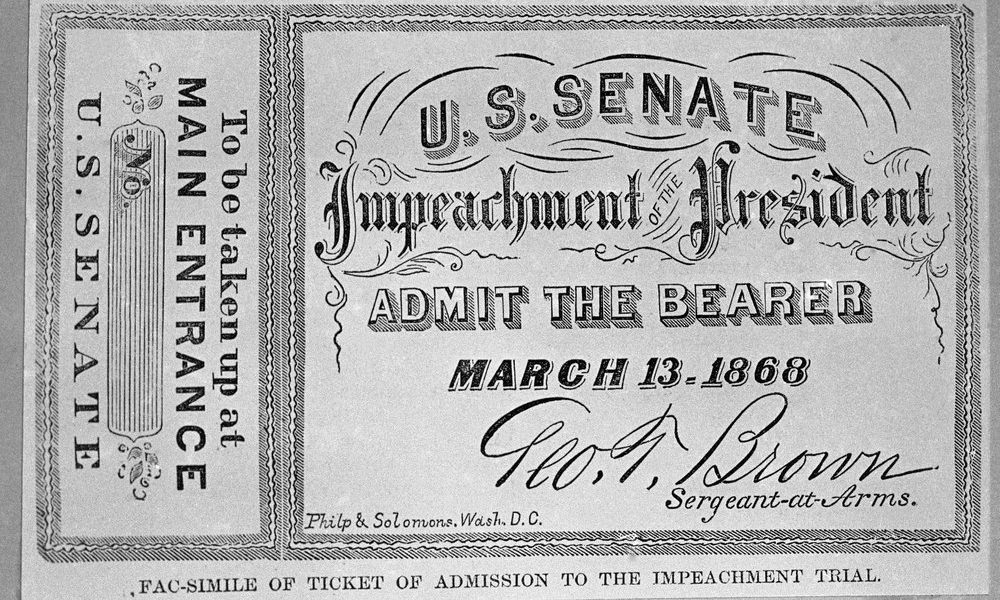

The examples of Andrew Johnson and Bill Clinton , who were both acquitted, offer insight into the process that Trump would face. Still, much remains unknown about how a trial would proceed, including what the charges would be. It’s also unknown whether witnesses would be called and whether parts of the proceedings would be conducted behind closed doors. Republicans who control the Senate will have a big say on both of those issues.

A look at what’s known about the impeachment trial:

IMPEACHMENT IN THE HOUSE

Formal articles of impeachment probably would be developed and approved by the House Judiciary Committee and then sent on to the full, Democratic-led House for a vote.

Not all proposed articles are certain to be adopted, even if Democrats control the process. The Republican-led House approved two and rejected two for Clinton. (In 1974, the House Judiciary Committee adopted three articles of impeachment against President Richard Nixon and rejected two others. Nixon resigned before the full House voted.)

ON TO THE SENATE

If impeachment articles are adopted, the House will appoint members to serve as managers who will prosecute the case in the Senate. For Clinton’s trial, Republicans on the House Judiciary Committee made the case against the president. One House manager was Lindsey Graham, now a senator from South Carolina.

Twenty years ago, the House managers walked silently across the Capitol to the Senate, where the sergeant-at-arms escorted them to the well of the chamber and Rep. Henry Hyde, R-Ill., then the House Judiciary Committee chairman, read the impeachment articles aloud. When he finished, Hyde said, “That concludes the exposition of the articles of impeachment against William Jefferson Clinton. The managers request that the Senate take order for the trial.”

It’s not clear whom Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., would appoint as managers, but one lawmaker who’s not on the Judiciary Committee seems a good bet: Adam Schiff of California, a former prosecutor who has been leading the impeachment inquiry as House Intelligence Committee chairman.

After impeachment articles are read, Chief Justice John Roberts would be sworn in to preside over the trial. Roberts in turn would swear in the 100 senators. Last time, they also signed an oath book and kept commemorative pens the Senate produced for the historic moment, though with an unfortunate misspelling: “Untied States Senator.”

THE PRELIMINARIES

The Senate has rules for impeachment trials, but some key questions, such as the length of the proceeding, are likely to be decided in negotiations between Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., and Sen. Chuck Schumer of New York, the Democratic leader. McConnell noted recently that their predecessors as leaders, Republican Trent Lott and Democrat Tom Daschle, hammered out agreements for Clinton’s impeachment trial.

One important issue to be resolved is who, if anyone, will be called as witnesses.

In Clinton’s trial, the House Republican managers sought to call witnesses. Democrats strenuously objected that this would drag out the trial. In the end, there were only three witnesses and no live testimony in the Senate: Monica Lewinsky, White House aide Sidney Blumenthal and Clinton confidant Vernon Jordan. All were questioned in private by both sides with a senator of each party present to keep order and resolve disputes. Excerpts of their videotaped depositions were shown at the trial.

HOW WILL THE TRIAL WORK?

In some respects, a Senate impeachment trial resembles a typical courtroom proceeding with a judge presiding and an unusually large jury of 100 senators. But there are important differences.

For one, it takes a vote of two-thirds of those present (67 out of 100 if everyone is there) to convict and remove the president from office. For another, while senators are jurors, they also set the rules for the trial, may ask questions and can be witnesses.

While courtroom jurors are screened for possible biases, voters already have selected the jury in elections that gave Republicans a Senate majority, with 53 seats. The GOP could insist on rules benefiting Trump, including limiting witnesses against him, though it would take just three Republicans to foil a party-line effort.

Even if all Democrats vote to convict Trump, the Democratic House managers still need to win over more than one-third of Republican senators for a conviction — a formidable task. By comparison, in the Clinton trial, Republican managers couldn’t win over a single Democrat and several Republicans voted to acquit.

To make their case, the managers are likely to give opening and closing arguments that could last for several days and respond to senators’ questions that also could be time-consuming. They also might question any witnesses. Trump’s defense team would have equal time to rebut the charges. Each step, as well as the time it takes to reach agreement on the rules, takes days, if not weeks.

COULD TRUMP TAKE PART?

Yes, but that would be unprecedented. Senate rules call on the person impeached, or a representative, to answer the charges. The Clinton legal team that handled those chores in 1999 included his top White House lawyers, but also Dale Bumpers, a former Democratic senator from Arkansas who was at ease in the chamber in which he served for nearly a quarter-century.

HOW LONG?

The Senate will determine the length of the trial. In theory, it could be cut off almost at the outset if a majority of the Senate votes to dismiss the charges. McConnell has suggested that is not likely, despite the Republicans 53-47 majority.

In Clinton’s trial, Lott, R-Miss., and Daschle, D-S.D., allowed Democratic Sen. Robert Byrd of West Virginia to move for dismissal a couple of weeks after the proceeding began, but it failed basically along party lines.

Clinton’s trial began on Jan.7, 1999. Each side had 24 hours to make opening arguments and an additional three hours for closing arguments.

Three weeks after the trial began, senators agreed that they would hold a final vote no later than Feb. 12. President Johnson’s impeachment trial lasted just over two months.

THE CHIEF JUSTICE

The chief justice presides over an impeachment trial of the president because the Constitution says so. The Founding Fathers took the vice president, who also is the president of the Senate, out of the equation, because the vice president would become president if the Senate convicts.

Roberts would decide questions of evidence and procedure that are not spelled out in Senate rules. But unlike in a courtroom where the judge’s ruling is final, the Senate can override Roberts’ decisions by a majority vote. When senators have questions for lawyers or witnesses, they submit them to the chief justice, who does the asking.

In the Clinton trial, Chief Justice William Rehnquist stayed above the political fray. There’s no reason to think Roberts would approach his role differently.

Rehnquist balanced his job at the court with his duties across the street at the Capitol, though the court was not in session for most of Clinton’s trial. On one day, when the court heard arguments and the trial was in session, Rehnquist ducked out about 10 minutes early during arguments over electoral districts in North Carolina. Walter Dellinger, an attorney arguing the case, said the lawyers were notified that Rehnquist would leave early, but nothing was said in the courtroom.

THE END GAME

Eventually, senators will deliberate. Whether that’s done in private is up to them.

In 1999, the Senate defeated a Democratic effort to open up deliberations. Once a decision has been reached, the Senate meets in open session to vote on each article of impeachment. Senators will stand one by one at their desks and offer their verdict, guilty or not guilty.

Twenty years ago, Republican House members could not persuade any Democratic senators to convict Clinton and they lost five Republican votes on one impeachment article and 10 on the other. Democrats have an equally tall order this time. To convict Trump, they need to draw 20 Republican senators, assuming all 45 Democrats and two Democratic-allied independents vote against the president.

If Trump is not convicted, the trial ends and he remains in office.

But if he is convicted, the country would enter an unprecedented situation. Trump would be automatically removed from office and Vice President Mike Pence would become president. It’s not clear how quickly the succession would happen, but the Constitution does not contemplate any gap between a Senate vote to convict and the new president assuming power. “In the case of the removal of the President from office or of his death or resignation, the Vice President shall become President,” the 25th Amendment says.