Minnesota

Minnesotans are drinking water contaminated by nitrate washed away from crop fields

MINNEAPOLIS (AP) — Years of unchecked agricultural pollution has led Minnesotans to drink tap water that is contaminated with unsafe levels of nitrate, a chemical associated with cancer and other serious health problems.

In a report released Tuesday morning by the Environmental Working Group, it was found that one in eight Minnesotans are drinking nitrate-tainted tap water, according to the Star Tribune.

The environmental group says Minnesota is on “the brink of a public health crisis.”

Nitrate, a chemical component in fertilizer and manure, is being washed away by rain and irrigation off crop fields and seeping into groundwater. Based on public records from the state Department of Health and Department of Agriculture, the nitrate contamination is far worse in privately owned wells, given they are not required to be periodically tested like Minnesota public water systems are.

“I think we would all be surprised how much nitrate is in these wells if we actually tested them,” said Anne Weir Schechinger, a senior economic analyst in the the organization’s Minneapolis office and co-author of the study.

Drinking water high in nitrate has been linked to different types of cancer, elevated heart rates and a potentially fatal condition known as blue baby syndrome in which infants are deprived of oxygen.

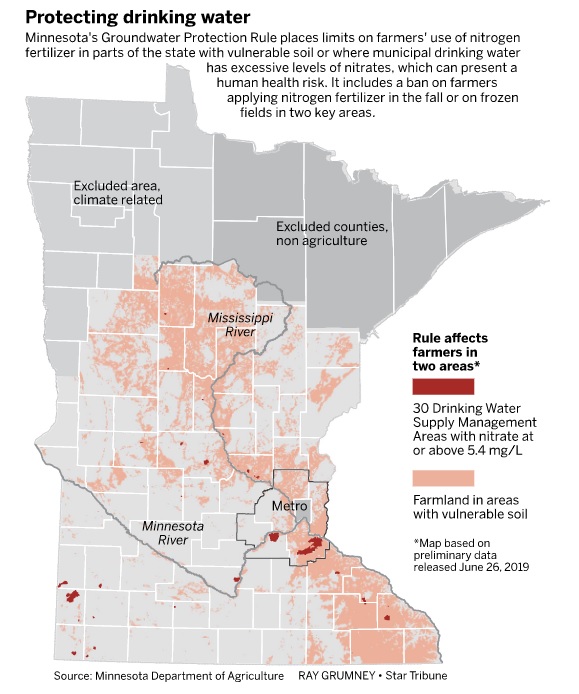

In efforts aimed to stop the use of nitrogen fertilizers, Minnesota implemented at the beginning of this year, the Groundwater Protection Rule.

It prohibits applying commercial nitrogen fertilizer in the fall and in drinking water supply management areas that already have elevated nitrate levels.

The rule also establishes an enforcement program encouraging farmers to adopt greener practices.

Farmers are in full support of the new nitrogen fertilizer restrictions but conservation groups and some agricultural experts criticize the new rule doesn’t address manure or contamination of private wells.

Retired University of Minnesota soils scientists Gyles Randall said a big miss in the rule is it only focuses on when commercial fertilizer is applied and not how much is applied.

The Environmental Working Group praised the rule as a strong first step, and said other states are watching to see how it’s implemented.